As a direct consequence of the electric-car market expansion promoted by Global North economies and China, lithium demand has skyrocketed over the past decade1. This boom has brought a rush not only for lithium, but also for what is most needed to make lithium extraction possible: water. In the Atacama Desert, a long history of mining cycles has left an evolving footprint of cumulative environmental damage that communities, activists, and scientists have denounced for more than a decade. Amid a global lithium fever, these territories have been given the misnomer the “Lithium Triangle” by companies, governments, and academics—a clear reflection of the colonial imaginaries that naturalize extractivism in Indigenous territories. Naturally, these territories are worth much more than lithium, copper, saltpeter, potash, or any other mineral extracted from their innermost parts. This explains why the rapid expansion of lithium extraction has been met with different forms of resistance across the Andean Puna and Altiplano, where communities, social movements, and scientists argue that salt flats are not mines, but rather wetlands.

My relationship to the Atacama Desert, one of the driest places in the world, revolves around water. When I first arrived in San Pedro de Atacama, I was amazed by the irrigation canals that make water flow across the town, villages, and ayllus.2 Friends and farmers, with whom I shared a transcendental part of my life, generously explained to me how the collective use of water makes the existence of farming lands, forests, and wetlands possible amid the desert. The presence of farmers and shepherds, I understood, not only depends on these hydro-agro-ecosystems but also produces the conditions for their very existence. This nonextractivist relationship persists despite the water privatization imposed during the Chilean dictatorship (1973–1990). Today, mass tourism and the mining of lithium and copper exert growing pressure on the region. This continuity has allowed me to understand that long-term resistances are sometimes quiet, just like the desert.

Common Struggles in the Lithium Mining Frontiers

Indigenous ancestral territories around the world continue to resist, in many different forms, colonization and occupation for corporate profit. The colonization of Indigenous lands does not slumber in history; it is an ongoing phenomenon that we witness in (not-so) far-away lands like Palestine, in what today is the Antofagasta region in northern Chile, and in the state of California in the Western US. In other words, Palestine, Antofagasta, and California are all sacrificial territories for the same imperial project.

As we have learned from our countries’ history and from the news every day, the colonial response to resistance against occupation and dispossession is genocide. Where dispossession has been achieved, the simultaneous exploitation of cheap nature and labor,3 local or migrant, is required for the completion of the accumulation project. But in the context of the corporate energy transition, dispossession also needs to be governed to make massive extraction and ecocide morally acceptable and fair to the same communities dispossessed of their lands, water, and sovereignty.

In the Puna de Atacama, the region spanning parts of Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina, the lithium fever has exposed the colonial logics behind green extractivism. As mineral demand surges, lithium projects are imposed by force or without consent. Across these territories, Lickanantay, Colla, Aymara, and Quechua Indigenous communities demand their right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) and proper environmental assessment. In this context, the Plurinational Observatory of Andean Salt Flats (OPSAL) emerges as a space for transborder solidarity, connecting the experiences of salt flat defenders and allied networks beyond the limits imposed by colonial borders. Through regular online meetings, collaborative research, and coordinated advocacy, the members of this collective have built a network based on trust and a profound attachment to the Andean salt flats and to all the forms of life they host.

OPSAL is linked to the Yes to Life, No to Mining (YLNM) network, an international solidarity space that connects and supports struggles for the defense of life over mining profit across the globe. In a context where more territories are affected by the lithium fever, not only in the Global South but also in the peripheral North, YLNM and other networks such as the Thematic Social Forum on Mining and Extractivism (TSF) have become more necessary than ever. Within these spaces, defenders and movements put into tension different valuations4 of nature, land, and water, resisting not only specific mining projects but also the hegemonic narratives of a business-driven transition that tries to reduce territories rich in culture and biodiversity to mere mineral deposits, like the aforementioned Lithium Triangle in South America, or the so-called Lithium Valley in California.

From Regional to Transnational Solidarity and Advocacy

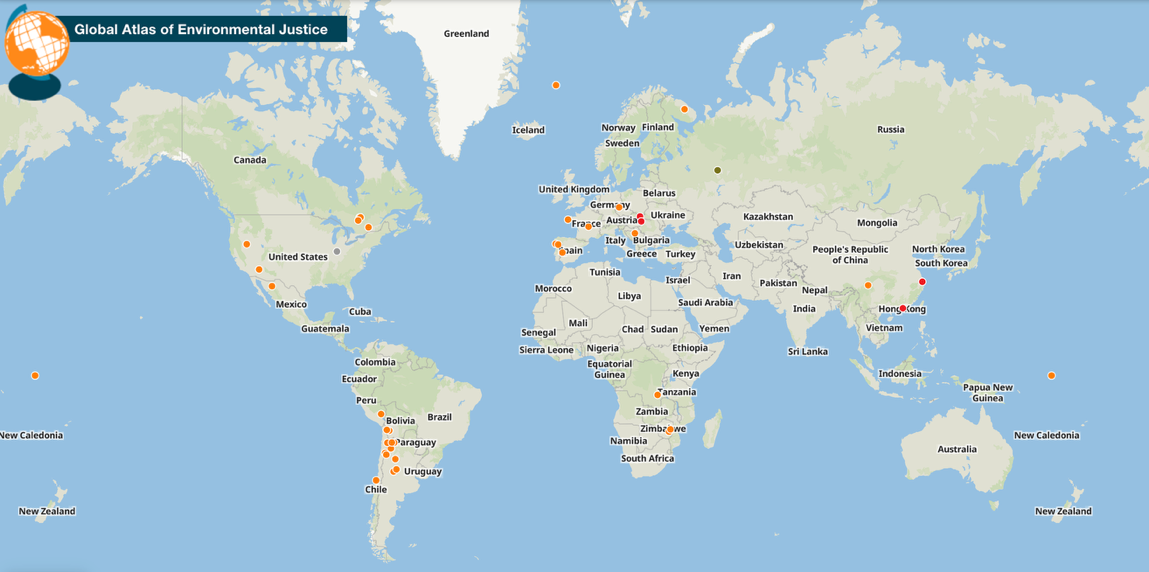

In 2020, I was invited to collaborate with an initiative from the Environmental Justice Atlas (EJ Atlas) aimed at mapping the environmental conflicts related to transition minerals. The results presented by the EJ Atlas team showed an updated image of the rapid expansion of lithium value-chain projects worldwide. A couple of years later, I had the opportunity to travel and meet with defenders, activists, and researchers in Jadar Valley, next to Rio Tinto’s proposed lithium project in Serbia. After visiting the local offices of the mining giant involved in several conflicts around the globe5, local defenders and guest organizations signed a declaration of international solidarity against green extractivism6, or the reproduction of the colonial extractive model justified by the energy transition of the most pollutant countries of the Global North. In 2023, along with members of the same group, I joined local farmers and activists at a yearly anti-mining camp in Covas de Barroso, Portugal. The following year, after attending a fantastic research seminar at the University of California, Santa Barbara, I also had the opportunity to visit the Salton Sea in California and meet local organizations Comité Cívico del Valle (CCV) and Imperial Valley Equity & Justice. Somehow, their stories reminded me of all of the stories I have heard before: Lithium mining needs (a lot of) water, and water is first and foremost required for life. More than the evident threat of lithium mining, I’d say that all of these organizations share a common sense of care toward water and the livelihoods of rural and Indigenous communities deeply connected to the land.

The Atacama and Sonoran deserts also share a common history of colonization of Indigenous territories presently divided by contested national borders. In both territories, lithium projects at different stages of development abut natural areas, primarily wetlands protected by local governments78 and, in the case of Chile, also by the Ramsar Convention, the UN’s international forum for the protection of wetlands worldwide.9 Farmlands are also vulnerable to lithium mining expansion. In Atacama, ancient Indigenous practices sustain a biodiverse oasis in the middle of the desert thanks to the community-managed use of the San Pedro River. Around the Salton Sea, the water from the Colorado River has shaped a territory characterized by extensive industrial crops that are consistently sustained by migrant workers. In both territories, different forms of agriculture coexist with extractive industries that pollute the air and water. The synergic and cumulative impacts of these activities, along with the lithium projects, threaten to transform these territories into green sacrifice zones10 pushed by private investors and local governments.

Mining stories are, when all is said and done, water stories. The ecocidal and genocidal project of green capitalism is resisted in many forms by those who see their livelihoods at risk in the light of lithium mining speculation. For this reason, local struggles are not necessarily for a just transition but rather for the right to a clean environment, water sovereignty, and, eventually, the legitimate right to say no to mining. Local communities, social movements, civil society organizations and researchers from all disciplines, cultural backgrounds, and geographies collectively create bridges of solidarity and shared knowledge across borders and continents. This knowledge is necessary not only to establish fair limits on extractive projects but also to lay the groundwork for territorially based socioecological transitions that prioritize environmental, climate, and water justice.

- See article: The ‘Alterlives’ of Green Extractivism: Lithium Mining and Exhausted Ecologies in the Atacama Desert. James J. A. Blair, Ramón M. Balcázar, Javiera Barandiarán and Amanda Maxwell (2024) https://brill.com/display/title/64309?language=en ↩︎

- Ayllus are Andean ancestral territorial units that today are organized as Indigenous communities. ↩︎

- Sofía Ávila-Calero, “Solar Capitalism: Accumulation Strategies and Socio‑Ecological Futures,” Sustainability Science 20 (March 2025): 1541–1556, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-025-01662-2. ↩︎

- Joan Martínez-Allier, “Mining Conflicts, Environmental Justice, and Valuation,” Journal of Hazardous Materials 86, nos. 1–3 (September 2001): 153–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3894(01)00252-7. ↩︎

- See theBusiness & Human Rights Resource Centre’s profile of Rio Tinto, accessed October 29, 2005, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/companies/rio-tinto. ↩︎

- Igor Todorović, “Jadar Declaration Unites Activists in Global Resistance Against Lithium Mining,” Balkan Green Energy News, July 10, 2022, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/jadar-declaration-unites-activists-in-global-resistance-against-lithium-mining.

↩︎ - “About Us,” Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.fws.gov/refuge/sonny-bono-salton-sea/about-us. ↩︎

- “Reserva Nacional Los Flamencos,” Corporación Nacional Forestal, accessed October 29, https://www.conaf.cl/parque_nacionales/reserva-nacional-los-flamencos. ↩︎

- “Sistema Hidrológico de Soncor del Salar de Atacama,” Servicio de Información sobre Sitios Ramsar, accessed October 29, 2025, https://rsis.ramsar.org/es/ris/876. ↩︎

- Gabriela Cabaña and Ramón Balcázar M., “Green Sacrifice Zones in Antofagasta: Chile’s energy transition promises decarbonization, but in the north of the country, a growing extractive frontier threatens water, land, and Indigenous ways of life,” NACLA Report on the Americas 57, no. 3 (August 2025): 286–294, https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2025.2542080. ↩︎