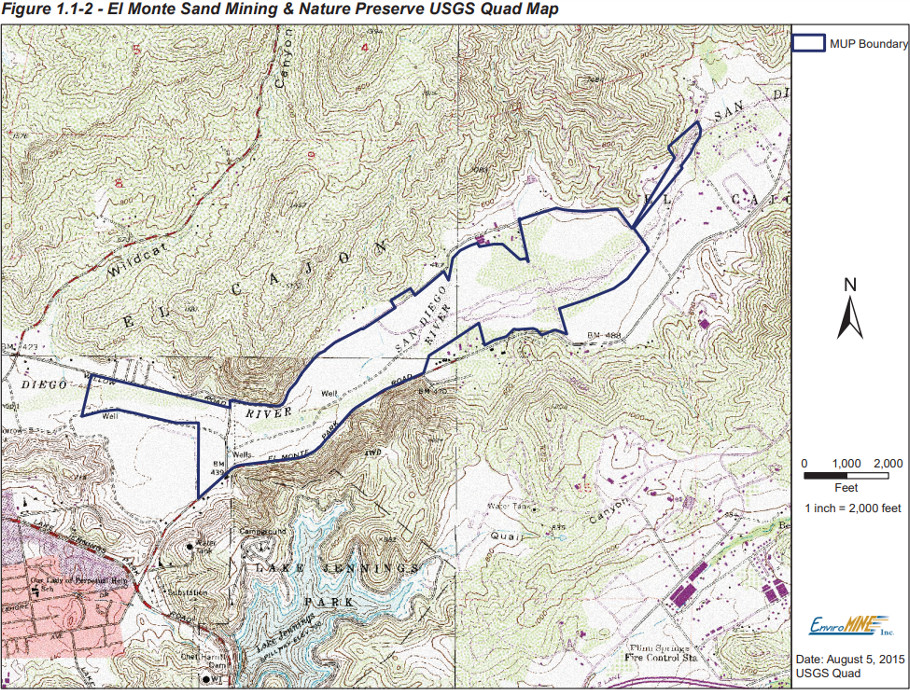

The San Diego River has the misfortune to generate a type of sand beloved by real-estate developers. It consists mostly of tiny pieces of rock rather than shell, which may be the key to its desirability. As a result, a proposed sand mine threatens to despoil the El Monte River Valley, a lovely fold of hills, trees, and water that lies hidden among the freeways and strip malls east of San Diego. The owners of the mine—a company registered under the misleading name of “El Monte Nature Preserve, LLC”—propose spending twelve years scooping out twelve and a half million tons of “construction-grade aggregate” from a five-hundred-acre stretch of the river valley, to a depth of around forty feet. Between 7 a.m. and 5 p.m., Monday through Friday, the company hopes to extract over five hundred tons of sand per hour, to be trucked away more than 150 times per day.

If approved, the proposed mine will damage a delicate ecosystem, impair air quality, inflict severe noise pollution, tear up an important Indigenous heritage site, and ruin an oasis of tranquility, biodiversity, and natural beauty. An environmental impact report compiled in 2018 “identified potentially significant environmental impacts to aesthetics (and land use), air quality, biological resources, cultural resources, mineral resources, paleontological resources, hazards (vectors), noise and traffic.”1 The project nonetheless continues to grind through the permitting process. Local activists have been organizing against it for years.

The proposal, filed more than seven years ago, triggered a battle over the meaning of the sediments of the El Monte Valley that continues to this day. For the mine owners, river sand is a profitable, extractible resource. For local settler residents, it is one element of a landscape that they value for health, beauty, and recreation. For environmental regulators, it is the focus of complex bureaucratic analyses. For elected officials, it is a symbol of their different ideological commitments and a bargaining chip in their political alliances. For tribal members, it is inscribed with deep cultural memory.

As the Potawotami scholar-activist Kyle Whyte has pointed out, the contested meanings of such landscapes are always about time as well as space. The fight for the future of the El Monte Valley is a particularly extreme example of Whyte’s contrast between the linear, divisible, interchangeable time units of industrial societies and the living, breathing, spiraling time of Indigenous kinship ethics. I say an extreme example because for the purposes of the sand mine, industrial time is not just linear and divisible, it is mechanically reversible. After the Valley has been scraped and plundered for twelve years, El Monte Natural Preserve, LLC proposes to put it all back together as part of a legally mandated remediation process. For them, the arrow of ecological time can move backward as well as forward. The El Monte Valley can be bulldozed for sand and then replanted. Destruction can be wrought and then unwrought.

But river sand is not “construction grade aggregate”; it is a variegated element in an infinitely complicated, ever-shifting, vibrant whole. The living valley cannot be disassembled and reassembled without tearing apart a complex web of human and more-than-human relationships that has evolved through millennia, back to the deep geological changes that produced its sand. Rivers are living palimpsests, inscribed by spiraling time, whose sediments should not be wantonly disturbed for the sake of suburban sprawl.

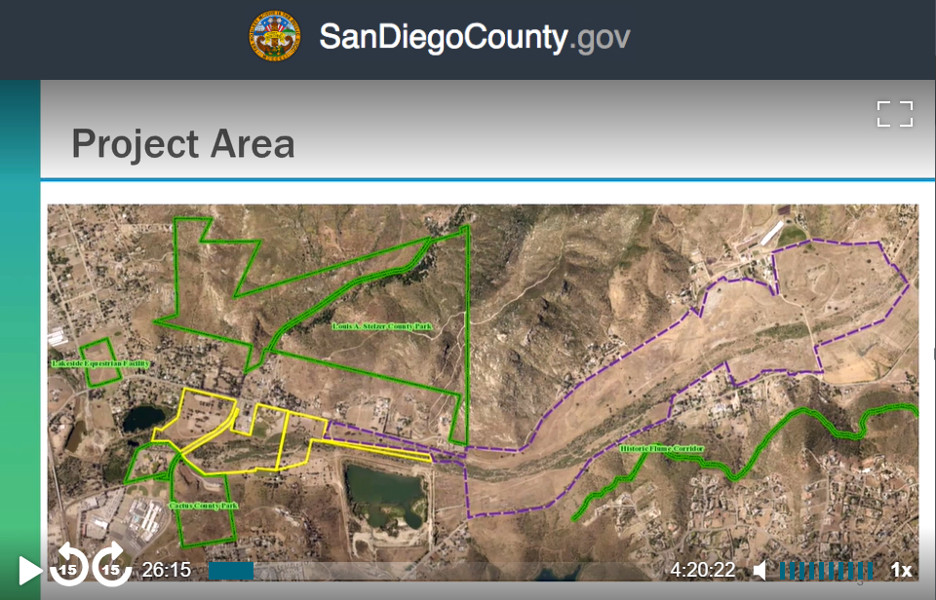

More prosaically, the battle over the meaning of the land has to do with different forms of property rights. Legally speaking, the El Monte Valley is an intact part of the vast settler commons the United States gained from Mexico in 1848. The five hundred acres of the proposed mine are owned by a state agency called Helix Water that has been supplying the region since 1885. The fact that it is a water commons and not private property makes the fate of the land more flexible and open-ended, providing openings for public groups to stake claims to its future.

The land lies within District Two, the largest of the five supervisory districts of San Diego County. Bounded by the county line to the east and the US-Mexico border to the south, District Two consists of a mixture of orchards, pasture, vineyards, factories, office parks, quarries, American Indian reservations, national forests, California state parks, and county open spaces. Lots of the land is unincorporated. Anza Borrego Desert State Park, the largest in the nation, covers six million acres. It’s beautiful out there. At the right spring season, you can drive from a butterfly-bedecked desert to glittering snow-covered peaks in a scant half hour. Even as the gentrifying City of San Diego leans further leftward, its sparsely populated hinterland remains a Republican stronghold.

In February 2021, I joined a protest walk against the sand mine. The demonstration was timed to fall a few days before a Board of Supervisors vote on the acquisition of a parcel of land adjacent to the proposed mine for an open space preserve. Although acquiring the land next door would not in itself stop the mining operation, it would encourage and embolden the resistance movement at an important juncture in the approval process.

The protest started in a parking lot. Bobby Wallace from the Barona Band of Mission Indians of the Kumeyaay Nation, veteran of the Standing Rock protests and an influential environmental activist, led the proceedings that day. After we had bought T-shirts and milled about a bit, Bobby called the demonstrators into a circle, delivered a short speech and a prayer to the earth, after which a group of singers, dancers, and percussionists performed Kumeyaay Bird Songs.

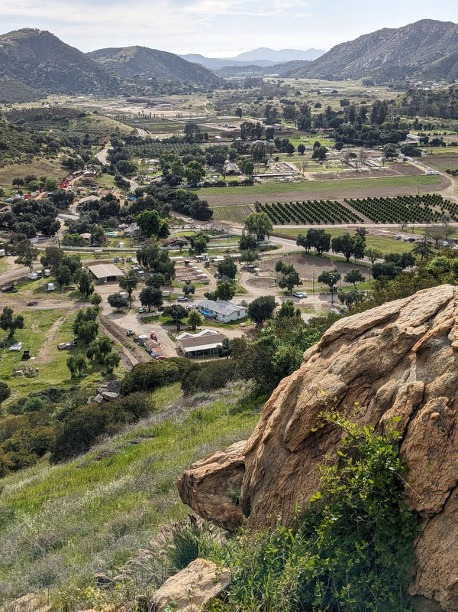

From the parking lot, we walked along the freeway, crunching through the broken glass and trash on the shoulder of the four-lane road, following the fluttering flag of the twelve Kumeyaay bands and Bobby’s banner showing the earth from space, cheering as cars honked in support. It was hot for February, and after a thirsty half hour along the roadside, we turned with relief into the lush seasonal green of the valley. A shaded trail led at length to a large meadow ringed by hills, where the demonstrators formed a wide circle with Bobby in the center. Holding aloft his trademark wooden staff, streaming this day with brown and white feathers, he talked about the significance of the San Diego River Valley as a vital corridor of communication and exchange linking tribes as far as the Four Corners area. Gesturing with his staff to the eastern horizon, he described a chain of Kumeyaay villages along the green ridge.

After he spoke, a white woman in the circle thanked him: “We have eight acres,” she explained, “and so we love this place.” Coming on the heels of Bobby’s summoning of Native history, her celebration of her privately owned eight acres demonstrated the inclusive nature of the coalition. The Save El Monte Valley campaign brings tribal activists together with equestrians, ranchers, landowners, polo players, urban environmentalists, and Little League parents to protect a beloved area of riparian habitat. Everyone with a stake in its conservation has a voice. Bobby’s stress on the precolonial cosmopolitanism of the valley as a communication and trade corridor is all of a piece with the campaign to preserve it as a shared natural commons.

A few days later, at the next San Diego County Board of Supervisors meeting, the main agenda item was the acquisition of the land adjacent to the mine. In keeping with his support for the sand mine, the District Two Supervisor, Joel Anderson, a right-wing Republican, argued that the presence of homeless encampments, trash, debris, and non-native vegetation in the valley meant that the purchase was a “bad deal.” His staff showed no photographs revealing the beauty of the site, but did offer four images of crumpled sleeping bags and battered tents.

After Anderson had made his case against the acquisition, the public comment period commenced. One after another, members of the Save El Monte Valley campaign offered detailed refutations of his argument. Speakers who all had different stakes in the valley talked about what it meant to them, including its significance to the Kumeyaay.

Silenced by the eloquence of the campaign, Anderson ended up sheepishly voting in favor of the purchase, which was approved five votes to zero.

A couple of weeks later, the same Board of Supervisors debated allocating funds for the restoration of the land. Bobby Wallace called into the meeting to reiterate the traditional importance of the Valley as an intertribal communication corridor. He also mentioned that his own children had played baseball on the Little League field. Activists then deluged the proceedings with comments referencing the significance of the valley to the Kumeyaay. The cogency and tight organization of their campaign vaporized any dissent, and the Supervisors voted unanimously to allocate $6.44 million to restore the land—more than double the purchase price.

In her book As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock, Dina Gilio-Whitaker characterizes such coalitions as “ways Native peoples are working in successful partnerships to protect land for sometimes different but ultimately mutually beneficial reasons.” Bobby Wallace’s understanding of the long history of the valley is the perfect framework for such a partnership, linking past, present, and future in a spiral of intergenerational relationships. Here is a letter that he wrote to the Supervisors:

It is the San Diego River that leads through the mountains with a trail system that spans to the 4 corners and as far south as South America and it was a place that my people the “Kumeyaay” had traveled, hunted, set up villages, lived life and death. . . . The valley is known to have cremation sites, and remnants of bones from my ancestors. It most likely has my DNA throughout the whole valley, as well as my Kumeyaay relatives on all Reservations in San Diego County and North County.

It is my wish, as well as many of my Tribal Member Friends and Family in San Diego County that the El Monte Valley remain as is, except for restoration to return it to its natural habitat. A conservation easement without disruption to the land is of most importance to keep the remains of our history intact, and be of most respect. Other than the Lakeside American Little League field, the land should be considered not only a natural habitat, but a sanctuary where there will never be any destruction as in digging for minerals of any kind in the future.

We are all fortunate to live in this beautiful place of many people, but we must remember that Mother Earth has been bleeding for way too long, and hopefully we won’t have to pay the price for her destruction.

Right before the vote to allocate funds for the restoration of the land, the District Three Supervisor, Terra Lawson-Remer, a dedicated environmentalist, proposed an amendment extinguishing subsurface rights and outlawing mineral extraction, in accordance with Bobby’s request.

Subsurface rights were devised in the 1850s to expedite mining and oil drilling. They divide land into a living surface above and a mineral estate below, a kind of legal scalping of the earth. When the Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to outlaw mineral rights on the new open space preserve, it confirmed that the El Monte Valley is not a source of raw materials for luxury housing but an ever-renewing landscape, sustaining life, pleasure, and memory for multiple communities. After that decision, the sand mine’s chances for approval plummeted to almost zero.

This victory underscores the vacuousness of the environmental protections afforded by the state. Consider the unintentionally comical second chapter of the Environmental Impact Report for the mine, titled “Aesthetics.” Defining a “scenic corridor” as “the land adjacent to and visible from the vehicular right-of-way . . . usually identified using a motorist’s line of vision,” the report admits that the “straight lines and uniform slopes of the finished slopes before revegetation would be more geometric than the naturally undulating lines that compose the current vistas of the valley.” Extraction transforms the idiosyncrasies of a particular place into interchangeable commodity units. Environmental impact reports do the same. Both break down complex living wholes into inanimate components for consumption.

The San Diego River is not there to provide a key ingredient of luxury housing. The beauty of the El Monte Valley is more than a pleasant vista for motorists. For those of us opposed to the mine, the Valley is a complex tangle of birds, fish, trees, reeds, vines, stones, wild animals, sand, mud, insects, the Little League, horse ranchers, hikers, Kumeyaay ancestors and their descendants, the Four Corners tribes and their descendants, us and all our descendants, human and non-human, generations into the future. Long may it thrive!

- El Monte Sand Mining Project, Public Draft, Environmental Impact Report, August 30, 2018. ↩︎